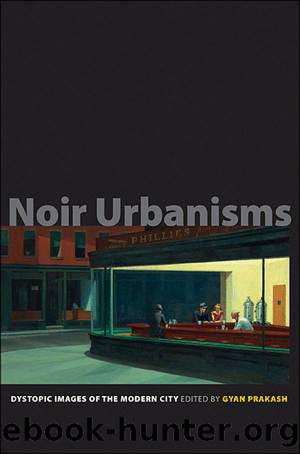

Noir Urbanisms by Prakash Gyan

Author:Prakash, Gyan.

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2010-06-15T00:00:00+00:00

Shifting Critical Forms

How do we make sense of these documentary and cinematic representations of Chinese cities? What do these images and the forms they deploy tell us about the large transformations within the history of critical forms in China? To begin, let me clarify that the two forms I have focused onâdocumentary and cinemaâare certainly not the only forms of critique deployed in contemporary China. There are other forms of critical reflection on society, government policies, and everyday life, including most noticeably the New Left intellectual discourses and the fragmented voices of disfranchised farmers, migrant workers, laid-off factory workers, and displaced homeowners. Overall, we can identify a significant shift in both the content and form of social critique from the high socialist period to the recent years of neoliberal restructuring that foregrounds the mass media.

During the first three decades of the socialist rule (1950sâ1970s), the Communist party-state maintained tight control over society, especially urban society. Its power penetrated deeply into the social fabric and worked through the heart of society (see Yang 1988). The party-state was able to mobilize the masses to engage in endless state-orchestrated political movements. As Dutton (2005) has convincingly argued, through a vital trope of the friend-enemy divide the Maoist regime was able to engender and harness constant political passion and commitment to ideological struggles, which defined Chinese revolutionary politics. In this era, social and cultural critique was carefully directed and monitored by the state. There was the rise of socialist propaganda that relied on political pamphlets, big-characters posters (dazibao), loudspeaker broadcasting in public space, revolutionary films, and party-organized political parades. The media, mainly in the form of radio broadcasting and the press, was brought under tight control by the authorities. Its mission was to serve the state and act as the âtongueâ of the party.12 Propaganda work became the primary channel through which to express the ideas of the party and to highlight the socialist utopia. A special government branch designated to take charge of propaganda work was established from the top ministry level to the grassroots level. The act of âcriticism and self-criticismâ played a central role in socialist political life, and such criticism had to be directed at the peopleâs enemies as defined by the party at a given time, at wrongdoing by others and self, or at shortcomings in the partyâs work rather than at the leadership or the party itself. It was dangerous to voice oppositional views that questioned or criticized the party-stateâs ideological standing and the socialist principles. Intellectuals during this period suffered greatly as they were more likely than others to express critical reflection and dissatisfaction with leftist politics.

The death of Mao and the rise of Deng Xiaoping created a new political climate. During the early 1980s, there was a flood of social critique primarily directed at the Cultural Revolution and the extreme leftist politics that devastated Chinese society. One of the most powerful forms was the âscar literatureâ (shanghen wenxue) that portrayed and critically reflected on the tragic experience of intellectuals and youth during the Cultural Revolution.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32019)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31942)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16029)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14076)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13370)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13366)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13242)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9343)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9292)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7314)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6622)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6281)